Ciencias Administrativas, Teoría

y Praxis

Num.

2 Año 12, Julio-Diciembre 2016, pp. 211-225

You love it, i love it, too: a social

network analysis approach to brand

love1

Lo

amas, yo también lo amo: las redes

sociales como enfoque en el análisis del amor hacia las marcas

Teresa Treviño*, Flor Morton**, Carolina Robles***

Abstract

Brand love is a person’s

emotional attachment to a brand. We

propose that brand love cannot be separated from the social context in which

it exists. This paper’s objective is to analyze how different

aspects of a person’s network

influence the love that a person feels toward a brand. Our research contributes to the

existing branding literature by identifying: a) the more a

person consumes a brand, the greater love the

consumer feels toward that brand; b) men and women love (or express their love)

for brands in significantly different ways, and women are likely to express or feel greater

brand love than men;

and c) differences in consumers’ ages have an impact on brand love. Additionally, by using a personal network analysis

approach, we conclude that people who love a brand and occupy a central position

in the participant’s network have a

greater influence on the participant’s

brand love. Furthermore, the results suggest that people of the same gender as

the participant will have a greater influence on the brand love that the

participant feels as well. Overall, these findings suggest that attitudes toward brands are socially

constructed.

Keywords: brand love, reference groups, social network analysis, homophily, centrality.

Keywords: brand love, reference groups, social network analysis, homophily, centrality.

Resumen

El amor

hacia una marca se refiere al apego emocional

que tiene un

consumidor hacia ésta. En

este trabajo, se

propone que el amor a la marca se debe de entender en el

contexto en el que este fenómeno existe. El objetivo del presente trabajo es analizar

cómo los diferentes aspectos de las relaciones personales de un consumidor influyen en el amor

que éste siente hacia una determinada marca.

Específicamente, nuestra investigación contribuye a

la literatura de

mercadotecnia al identificar que: a) Entre más se consuma una marca,

mayor será el apego emocional del consumidor hacia

ésta; b) los hombres y las mujeres aman (o expresan

su amor) a las marcas de diferentes maneras, siendo

las mujeres quienes tienen

mayor probabilidad de expresar el amor hacia

una marca; y c) las diferencias en las edades de los consumidores influyen en el amor hacia las

marcas. Adicionalmente, mediante un análisis de redes

personales, se concluye

que los consumidores que aman a una marca y que

ocupan una posición central en la red del participante, tienen mayor influencia

en el amor de marca que siente el participante.

Además, los resultados sugieren que la

igualdad de género entre participante y personas en su red, tiene mayor influencia

en el amor de marca que

1 Un resumen

del presente artículo fue presentado y publicado en la memoria del Tercer Coloquio

de Mercadotecnia de la EGADE Business School efectuado en Monterrey, Nuevo León, México, el 12 de Diciembre, 2013.

* Doctora en

Ciencias Administrativas, Profesora de Cátedra, Tecnológico de Monterrey. E-mail: ttreviño@itesm.mx

** Doctora en

Ciencias Administrativas, Profesora de Cátedra, Tecnológico de Monterrey. E-mail: flormorton@itesm.mx

*** Maestra en Mercadotecnia, Candidata

a Doctorado en Ciencias Administrativas, Tecnológico de Monterrey.

E-mail: crobles@tca-ss.com

Artículo recibido: 5 de febrero de 2016

Artículo aceptado: 10 de junio de 2016

dicho

participante siente. En general, estos resultados sugieren que las actitudes hacia las

marcas – especialmente el amor de marca

- se construyen socialmente.

Palabras clave: amor de marca,

grupos

de referencia, análisis de redes sociales, homofilia, centralidad.

Clasificación

JEL: M30

Introduction

Brand love

is a concept

that encapsulates the

relationship between consumers and their brands, how

this relationship is

developed and strengthened, and the consequences of this relationship. According to the

literature, brand love is equivalent to interpersonal love; a person falls in love with a brand

due to its qualities, and this love can then grow over time (Batra, Ahuvia, & Bagozzi, 2012). Previous

research has focused

on studying brand love as an individual behavior that a

person develops. Other research has addressed the antecedents and consequences

of brand love, such as brand loyalty and positive word-of- mouth (Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006).

However, what remains unclear is how other

individuals influence consumers in

this area, encouraging them to fall and/or stay in love with a brand. We propose that brand love cannot be

separated from the social context in which it exists.

The literature on reference group theory

is a

relevant basis for this research. It is said that people

tend to compare themselves with others because the latter serve as a source of

information that facilitates decision-making and

criteria selection. Using

reference group theory to analyze consumer behavior

is interesting, as previous

research has shown that there is congruency between group membership and brand

usage (Escalas & Bettman, 2003).

Some concepts

from social network theory can also be used to examine

how the characteristics of the members of a person’s network influence this person’s decisions with respect to brands.

More specifically, homophily, which suggests that people with similar

characteristics tend to interact more frequently,

and centrality, which recognizes the influence of the

most central person in a network, may be relevant to the concept of brand love.

Additionally, concordantly to literature on social networks, in

this paper we refer to the focal node

as “ego” and “alters” to

the nodes to which the ego is directly connected

(Borgatti, Mehra, Brass, & Labianca, 2009).

This

paper’s objective is to analyze how different aspects of a person’s network

influence the love that this person

feels for a brand. In our

research, we attempt to understand how the characteristics of the members in a

person’s close network affect the love that this person feels for

a brand.

This paper

is structured as follows. The first section addresses the literature

on brand love and references concepts from group theory and social network

theory that help to form a foundation for the present

research. The second section presents the methodology used to collect and analyze the data.

The third section presents the results

of the statistical analysis. Next, the findings are discussed. Finally, the implications of the results are

described, and possibilities for further research are suggested.

Literature

review

Brand

love

The choice

of one brand

over another presents an opportunity for consumers to show

themselves to others as they are or as they wish to be (Parker, 2009). Brands reinforce how consumers

see themselves; consumers choose brands that are congruent with their

self-image (Maehle, Otnes, &

Supphellen,

2011). Self-congruity

theory explains that consumers prefer

brands that have a symbolic meaning that matches their self-perception;

consumers become more emotionally attached to brands that are congruent with what they are,

want, or wish to be (Govers & Schoormans,

2005; Sirgy,

1982).

Aaker and

Fournier (1995) argued

that “the brand is treated as an active, contributing partner in the dyadic

relationship that exists

between the person

and the brand” (Aaker & Fournier, 1995,

p. 393). Previous

research has established that consumers develop

a sense of security by

creating connections with their brands

and that they

develop relationships with their

brands as they do with other people (Fournier,

1998). Brand love is a feeling within the consumer-brand relationship and is

often described as having elements, characteristics, and dimensions that are

similar to those of interpersonal love (Batra et al., 2012).

According to Batra et al. (2012),

the elements of the brand

love prototype are antecedents, the core, and consequences. The antecedents

of brand love are what cause consumers

to fall in love with a brand: the brand’s

exemplary qualities (Batra, et al., 2012). The core of brand love is the consumer’s

feelings for the brand, and the elements of the consumer- brand relationship that might deepen

that bond are: (1) strongly

held values and existential meaning, (2) intrinsic rewards, (3) self-identity, (4)

positive affect,

(5) passionate desire

and a sense of natural fit, (6) emotional bonding and anticipated

heartbreak, (7) willingness to invest, (8) frequent thought and use, and (9)

length of use (Batra, et al., 2012). Finally,

the consequences of brand love are the consumer actions and

intentions that are

associated with brand love: (1) repurchase intentions, (2) willingness

to pay a higher price, (3) positive word-of-mouth (WOM), and (4)

resistance to negative information

(Batra, et al., 2012).

Because the

repurchase or frequent use of items by a particular brand reflects

a consumer’s loyalty to the brand and because consumer loyalty

is highly correlated with brand love (Carroll &

Ahuvia, 2006), we hypothesize that the

more a person visits or consumes the brand´s beverages, the greater his/her

brand love for that company will be.

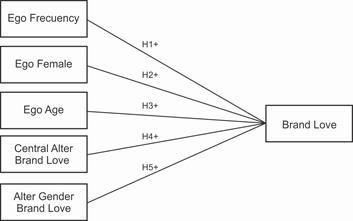

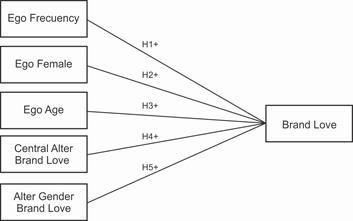

H1: The more the ego

visits/consumes the brand (Ego Frequency), the greater the ego’s brand love.

Past

research suggests that men and women differently

express emotions such as happiness, sadness, loneliness, and

love,

indicating that women tend to

express these emotions more than

men do (Balswick

& Avertt, 1977; Brody, 1985; Simpson

& Stroh,

2004). For

example, the results of a study of the gender differences in self-rated emotional expressiveness show

that, in general, women have

significantly higher confidence in expressing their love or affection to males than vice versa (Blier

& Blier-Wilson, 1989). Additionally,

because previous research in marketing describes brand love as having

characteristics, elements, and

dimensions that are similar to those of interpersonal love (Batra et

al., 2012), we believe that men and women will also differently

express their love of particular brands. More

specifically, we hypothesize that

women will express greater brand love than men.

H2: Women (Ego Female) will be more likely to express brand love than men.

Other

research about brand behavior and choice has shown that age is positively

related to brand loyalty, which means that older people tend to exhibit more loyal behavior

toward brands. Previous studies about age and brand behaviors show

that “middle-aged” people are more likely to express high

loyalty to brands (Wood, 2004).

Because loyalty is one variable that is related to brand love,

indicating strong attachment to a particular brand, we propose that this

age-loyalty phenomenon can also be applied to brand love.

Therefore, we hypothesize the

following:

H3: The older the ego is (Ego

Age), the more brand love the ego will express.

Reference groups

A reference group can be described as a social group that is

important to a person and against

which he or she

compares himself or herself.

Using reference group theory to analyze consumer behavior

is interesting given that previous research has shown that there

is congruency between

group membership and brand usage

(Escalas & Bettman, 2003). Because consumers use other people as

information sources, they also evaluate

their

beliefs and decisions by comparing those

beliefs and decisions with those of other individuals. We argue that consumers actively construct

their preferences and, more importantly,

their love for brands using their reference groups as

a source of information.

This conjecture is based

on the theory that people tend to behave

in a manner that appears consistent with the choices of the social group to

which they belong.

Two types of reference groups have been identified in previous research. The first group is the

normative referents, which include parents, peers and teachers. Because the

members in this group interact directly,

they influence the individual’s attitudes,

values and norms. Research

has proposed that family members in particular are likely

to be of greater importance to the individual because individuals tend to

identify more closely with their families. The second group comprises the comparative referents, which include

people such as celebrities and professional athletes. Although individuals do not have direct contact with these referents, they

provide aspirational behaviors and standards that others emulate (Childers

& Rao, 1992).

The literature

also suggests that

society can influence purchase decisions. Specifically for products

that are classified as high in social

involvement, the influence

of one’s social group on brand

choice has been found to be significant (Witt & Bruce, 1972). Because the

selected brand for this study

can be considered a brand that involves socialization, we propose that the

influence of the group members in a person’s close

network and the degree to which

those members love this brand will influence

that person’s brand love. In other words, if A (ego) has close friends, family, or coworkers (alters) who love this brand, the more likely it is that s/he will love the brand as well.

Social networks

Centrality

Centrality is one of the most important structural attributes of social networks. The concept of

centrality has been

widely

discussed,

and

it can be described as the node or point

in a network that occupies the most central position. A person who is positioned

on the central node is expected

to be structurally more

central than any other person in the network (Freeman, 1978). There are several

measures that can be used to analyze centrality, such as degree, betweenness, and closeness.

The concept of centrality is relevant

to this research because we suggest that a person’s structural position will help to determine his/her level of

influence. For example, if A is a central person in

the network of his/her friend B, then A will influence B to a greater degree. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H4: The more central the network position

of an alter who loves the brand (Central Alter Brand Love), the greater the brand love of the ego.

Homophily

Homophily is a phenomenon

in which contact between similar people

occurs more frequently than contact among dissimilar

people (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). This concept is especially interesting in the context of this

research because we are attempting to study how people who engage in a specific

behavior (consuming one brand and loving

it) influence another person’s brand

consumption and love. Previous

research has found that the demographic characteristics of a

person, such as age and gender,

usually show substantial homophily (McPherson, et. A., 2001). In other

words, people of the same sex and age will tend to interact more frequently. In a study of young boys and girls, it

was found that boys tend to play

with other boys

and that girls tend to socialize with other girls.

Interestingly, girls were shown to

interact with smaller and more homogeneous groups (McPherson, et. Al., 2001). With

respect to age, studies have also shown that social groups tend to form based on their members’ ages and that these groups may vary depending on the

type of ties involved. In the case of friendship, age is one of the dimensions that seem to have a stronger

influence on homophily (McPherson, et al.,

2001). Taking

previous

findings

about

age

and sex

into consideration, we

hypothesize that because women tend to have smaller, more homogeneous and closer networks,

the members of their group will influence their brand love decisions to a

greater degree.

H5: If the alter is the same gender as the ego, the more the alter loves the brand (Alter Gender

Brand Love), the greater the ego’s

brand love.

Finally,

because the interaction

between the variables is relevant, we also hypothesize that brand love can

be understood in terms of several variables, as the following hypothesis

describes:

H6: Brand love depends on (a)

Alter Gender Brand Love, (b) Central Alter Brand Love, (c) Ego Frequency, (d) Ego Age,

and (e) Ego Female.

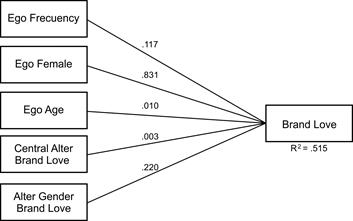

Figure 1: Brand love

proposed model

Methodology

To

test our hypotheses, we used a personal network analysis methodology. The three

authors conducted individual interviews with the study participants as part of the data collection

process. Individual responses were documented using the EGONET program, a software

program that was designed to collect and analyze egocentric network data. This

program facilitated the creation of the questionnaire and the data collection

process while also providing general global network measures that

we used for

further analysis in SPSS. We

selected a popular American

coffeehouse brand as the focus of our analysis because this brand has several

important characteristics. First, because

of

its

more

than 23,000

stores

worldwide,

the

brand

is

considered a well-known brand in

Mexico and around the world. All

of the participants in the study

were very familiar

with the brand,

even if they were non-users or non-frequent users of

the brand’s products. Second,

this brand is characterized

for being an enabler and promoter of social interaction between people;

achieved by the special and personalized experience they provide in all their

store locations.

A

basic

procedure

for

network

data

is

to get respondents (egos) to identify other people (alters) to whom they are

directly related and then to ask the ego if the alters

are related in some way (Borgatti et al., 2009). Therefore, in this research

participants were asked several questions

about their brand love

for this particular brand and were asked

to name 15 persons (alters) with whom they interact often. Then, answers to questions about each alter and his/her

attitudes toward the brand were recorded, along with answers to questions about the interactions between the participant-alter pairs. To conclude

the interview, the

network graph was shown

to the participants and then discussed. In general, all of the participants

agreed that the social groups to which they belonged were accurately represented. In total, 40 participants

were invited to be part of the experiment following a convenience and snowball

sample technique. Since each of the 40 participants (“egos”) answered

information about other 15 people, we have information about 600 alters. The

interviews were conducted by the three authors, in the city of Monterrey, Mexico. This city is characterized by having strong influence

by the US culture, due to the closeness to the American border. Additionally, all participants belong to a medium-high socioeconomic status.

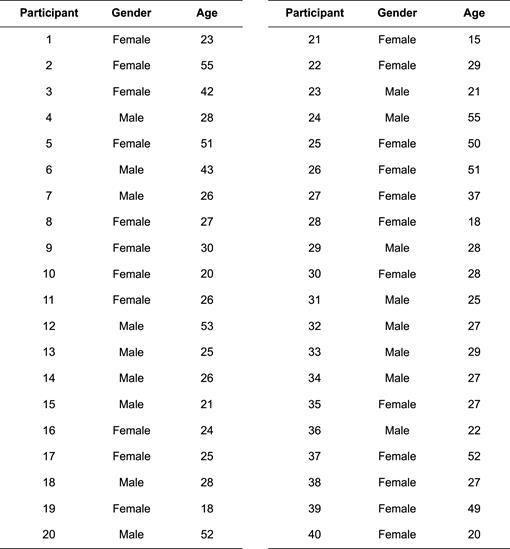

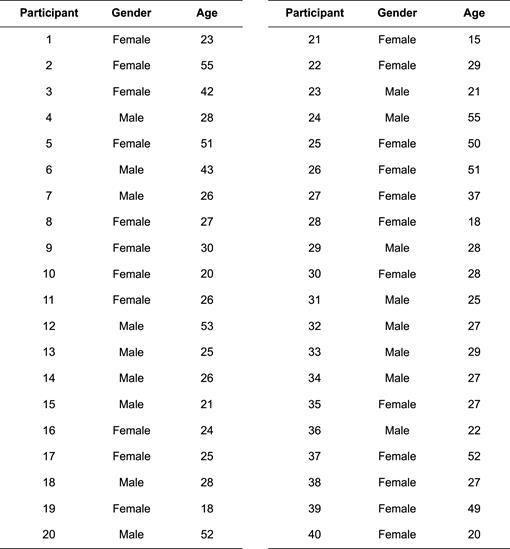

The distribution of the sample

was 42.5% male and 57.5% female; their ages ranged

from 15 to 55 years, with an average of 32 years

(SD =

12.05) (for additional demographic information, see Annex1). The participants’ responses

were later grouped and

analyzed using a

series of linear regressions

in SPSS to

determine the influence of several variables on brand love and the frequency of consumption of the

brand’s products.

The

interview was divided into three sections. First, the participant’s personal information was collected,

such as demographics and frequency of attending the brand’s

stores. Additionally,

this part of the

interview also focused on measuring brand love. For this construct, items

were selected from previous

instruments that were intended to measure brand love

(Carroll

&

Ahuvia,

2006; Batr et

al., 2012). More specifically, six

items were used to measure brand love in this research: a) Ego Love (How much do you love to go to this brand’s stores?), b) Ego Wellbeing (How good does going to this brand’s stores make you feel?), c) Ego Happiness

(How happy does going to this brand’s

stores make you feel?), d) Ego Fan (How much of a this

brand’s fan do

you consider yourself?), e) Ego Competition (When you are searching for a coffee shop, how often do you wait until you find this brand’s stores instead of going to the first coffee shop you see?, and f) Ego Price (Do

you feel this brand is worth the higher price?). All items were measured using

a five-point Likert scale. As the original

instruments were in English,

we used qualitative

approaches to construct our instrument: collaborative approach and back

translation to capture the same essence of the questions in Spanish (Brislin,

1976; Douglas & Craig, 2007). Although our

sample is small, and therefore

this study may be considered as explorative in

nature, a reliability test was conducted to determine whether these items

measure brand love as intended. The Cronbach’s Alpha was

.923,

which suggested that the items used in the questionnaire could be used to

obtain a valid measure of brand love.

The second

part of the interview considered the network information, in

which participants were asked to mention fifteen persons (also known as

“alters”) that he/she considers his/ her

closest relationships. We specifically asked participants to mention

people from different activities and

groups in which they belong, in order to improve the criteria of independence of observations.

Additionally, several

characteristics for each of the “alters” were

collected, such as

age, gender, type and strength

of relationship, and the extent to which the participant believe

this person (“alter”) loves the brand under study. Finally, the software

EGONET allows us to question

whether different pairs of the

mentioned alters are likely to interact without the person (ego) being present. This is especially useful to

construct the network and relationships around the main participant. To see the complete

interview questions, please see Annex

2.

Results

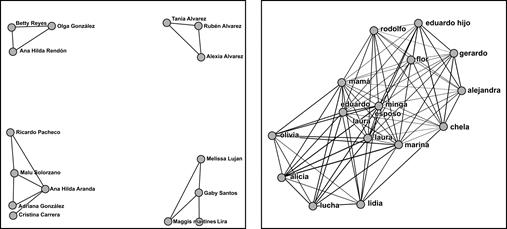

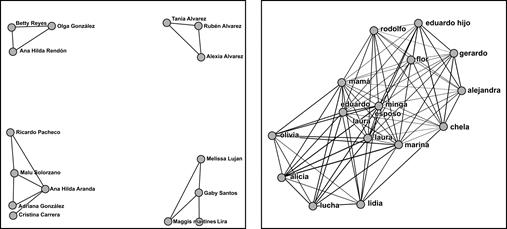

Analyzing the individual networks of participants revealed some similarities among the

participants; however,

the participants also differed in important ways that are worth discussing. For example, two types of networks

were identified.

On the one hand, we identified a very dispersed network in which two or more

groups were clearly separated (See Figure 2). People in one group were not connected

to people in the other groups. The participants who were members of this type of network were

usually involved in several activities that did not require interaction among

people in various groups. On the other hand, there were

also participants who reported

belonging to very close networks

in which all or nearly

all of the people knew each other or interacted in some way amongst themselves (See Figure 3). Participants who were members of this

type of network usually had one main activity in which they could involve family, friends and other acquaintances.

Figure 2: Dispersed

network Figure 3: Single group network

To test H1, H3, H4, and H5, we conducted correlation analyses for

Ego Brand Love and Ego Frequency (H1), Ego

Age (H3), Central Alter Brand Love (H4), and Alter Gender

Brand Love (H5). The results

of these correlation analyses show significant

(p=.000) positive correlations between each variable and brand love, providing

support for the four hypotheses (See Annex

3).

To test H2, we compared the means for brand love for men and women. The results of a Student

t-test show that there are significant differences between the two groups’

means for brand love (p=.000), with a mean of 2.382 (SD=.764) for the

men and 3.688 (SD= 1.199) for the women. This finding provides support for H2, suggesting that women show

greater brand love than men.

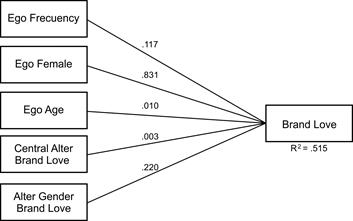

Finally, to test H6, we conducted a multiple

regression analysis with brand love as the dependent variable and Alter Same Gender

Brand Love, Central Alter Brand

Love, Ego Frequency, Ego Female, and Ego Age as the independent variables. The model was run

using 600 observations (previously explained); this model explained a

considerable percentage of the variation in the dependent variable, with R2 =

.515. In addition, all of the

independent variables were significant at a .01 significance level (See

Annex 4 and 5). More specifically, based on the coefficients of the regression we found that:

(1) the more the ego visits/consumes the

brand, the more the ego’s brand love (ßegofrecuency= .117, t=6.806, p<.01); (2)

women expressed more brand love than man (ßegofemale= .831, t=10.736,

p<.01); (3)

the older the ego, the more brand love (ßegoage=.010, t=3.211, p<.01); the more central an

alter who loves the brand, the more ego’s brand

love

(ßaltercentralbrandlove=

.003, t=3.693, p<.01);

and

(4)

the

more

an

alter of the same gender as the

ego loves the brand, the more the ego’s

love for the brand (ßaltersamegenderbrandlove=.220, t=10.379, p<.01). (See Figure 4 for the complete model).

Figure 4: Brand love

model

Discussions

and conclusions

To understand how other individuals encourage consumers to fall in love and/or stay in love with a brand, we analyzed the different

aspects of a consumer’s personal

network. Based on this research, we conclude that the love that

consumers feel toward

a brand is influenced

by others, and more specifically, by

the characteristics of the persons in their network. These findings are

congruent with reference groups literature, as previous studies have

suggested that decisions

to select a

brand can be influenced

by society, especially when the

brand is classified as high in social involvement, or is publicly

consumed (Childers

& Rao, 1992).

Additionally, previous research suggested that the construct of social identity within

a brand community context, influence brand identification.

This phenomenon occurs because increased identification with a particular brand

community or group leads to greater involvement with the brand (Bergkvist

& Bech-Larsen, 2010). In line with these ideas,

this research is one of the first

to consider and measure the consumer’s close social ties and analyzes their

influence on brand love.

In

the first phase of our study, we

analyzed the personal characteristics of the ego that influence his/her brand

love toward this brand. First, we found that the more the consumer

visits/consumes the brand, the more brand love the

consumer feels for the brand. This finding supported

our theory regarding

brand love and repurchase

intentions (Batra, et al., 2012; Carroll &

Ahuvia, 2006). More specifically, literature has suggested that consumer

trust and satisfaction with a brand have an impact on purchase intentions

(Zboja

&

Voorhees,

2006). Findings

of this research

allow us to

expand this

knowledge, by considering

not only satisfaction and

trust as determinants of repurchase intentions, but

also stronger emotional bonds - brand love.

Additionally, this results

may offer managers the vision that

focusing on developing more emotional bonds with their consumers is important to achieve

desirable post-purchase behaviors (Carroll &

Ahuvia,

2006).

Second,

we found that men and women love (or express their love) significantly differently, and

that women are

more likely to express or feel

brand love than men are. This is congruent with previous

literature

on gender and brand relationships, as it has been identified that women exhibit more and stronger interpersonal

relationships and brand involvements

(Fournier, 1998). Finally, consistent with the brand loyalty

literature, we concluded that the older

the consumer is, the more

likely it is that s/he will feel and/or express brand love.

In

the second part of our research, we analyzed the characteristics of consumer

networks that might

influence their love

for the brand. First, we analyzed the centrality of the alters because the most central person in a network may have more influence than

the other network members

(Freeman, 1978). In a

consumer’s

(an ego’s) personal network, the central person (the central

alter) is the one who occupies the middle of the ego’s network, and this individual has a higher probability of

knowing and interacting with the rest of the alters. Validating this centrality theory, we conclude that if an alter who loves a brand has a more central network position,

the ego will feel greater love for the brand. Second, because people with

similar characteristics tend to interact

more frequently with each other (homophily), (McPherson, et. al,

2001), we concluded that if the alter is

the same gender as the ego, then the more the alter loves the brand, the

greater the ego’s brand love will

be.

Overall,

the proposed model explains how consumers’ personal and social (network) characteristics influence brand

love. We conclude that all of the

previously discussed variables combine to influence the brand love that consumers

feel. These variables include how frequent the consumer

visits/consumes the brand, whether the consumer is a man or a woman, the consumer’s

age, the brand love of the central alter,

and whether the alter is the same gender as the consumer.

Implications, limitations and future research

The findings

obtained in this study may have important theoretical and

managerial implications. In suggesting

that attitudes toward brands are

socially constructed, we attempt to contribute to brand love theory by

generating discussion and further research on this topic. Hopefully, the research

presented in this paper will represent one of the first of many attempts

to consider the social influence that people have on other individuals’

feelings and emotions about brands. Managers and marketing practitioners can

also benefit from this paper’s results.

If it is understood that brand

love develops from consumer interactions with others, specific communication

strategies can be designed that promote social gatherings related to the brand.

Naturally, this research is not without

limitations. First, a

relatively small sample was

used in this first attempt to

study this phenomenon. Additional analysis

with a larger sample of personal networks may generate more conclusive

results. Second, because the methodology employed in this investigation was

quantitative, we were unable to develop a full understanding of the phenomenon

at play. Future research

could use an emic approach to study how a person’s network influences his/her brand love.

Finally, because the participants

answered questions about their perceptions of the feelings that the members of

their networks had

about the brand,

we did not directly measure the alters’ brand love. This is a popular methodology for social

networks studies, however, our

database of 600 observations was constructed by 40 participants that

answer questions about their

known alters. Additionally, we cannot ignore the fact that people from the

same “group” or network tend to be similar among them, meaning that they are

likely to not be independent observations per se. Considering all this, our results should be treated as explorative in nature, emphasizing the overall

hypotheses of this paper. Therefore, next steps for this research could

consider directly interviewing the members of each participant’s

network to

explore the entire network, and/or utilizing other complex statistical analysis

to obtain a more accurate measurement of the construct.

Finally, this research could also be expanded through analyses of other brands that have fewer social

implications, such as

toothpaste brands. These brands are not

consumed during social interaction; however,

close family and friends may still recommend these brands. If such research is conducted,

it will

be interesting to

compare the results for brand love that are obtained for

different product categories.

References

Aaker, J., & Fournier, S. (1995). A Brand as a Character, A Partner

and a Person: Three

Perspectives on the Question of Brand Personality. Advances In Consumer

Research, 22(1), 391-395.

Balswick, J., & Avertt, C.P. (1977). Differences

in Expressiveness: Gender, interpersonal orientation, and

perceived parental expressiveness as contributing

factors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 39(1),

121-127.

Batra, R., Ahuvia, A., & Bagozzi,

R. (2012).

Brand Love. Journal Of Marketing, 76(2),

1-16.

doi:10.1509/jm.09.0339

Bergkvist, L., & Bech-Larsen, T. (2010). Two studies of consequences and actionable

antecedents of brand love. The Journal of Brand Management, 17(7), 504-518.

Blier, M.J., &

Blier-Wilson, L.A. (1989).

Gender differences in self-rated

emotional expressiveness. Sex Roles, 21(3-4),

287-295.

Borgatti, S.P., Mehra, A.,

Brass, D.J., & Labianca, G. (2009). Network

analyses in the social

sciences. Science, 323, 892-

895.

Brislin, R. W. (1976). Translation: Application and Research.

New York: Gardner Press

Inc.

Brody, L.R. (1985).

Gender differences

in emo- tional development: A review of theories

and research.

Journal of Personality,

53(2), 102-149.

Carroll,

B.A.,

& Ahuvia,

A.C. (2006). Some

antecedents and outcomes

of brand love.

Marketing

Letters, 17, 79-89

Childers, T. L., & Rao, A. R. (1992). The

influence of familial and peer-based reference

groups on consumer

decisions. Journal of Consumer

research, 198-211.

Douglas, S.

P., &

Craig,

C.

S.

(2007).

Collaborative and iterative translation: An alternative approach to back translation. Journal of International Marketing, 15(1),

30-43.

Escalas,

J.

E.,

&

Bettman,

J.

R.

(2005).

Self‐construal,

reference groups, and brand meaning. Journal

of Consumer Research, 32(3),

378-389.

Fournier, S. (1998).

Consumers and Their Brands: Developing

Relationship Theory in Consumer Research. Journal Of Consumer Research, 24(4),

343-373.

Freeman,

L. C. (1979). Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Social networks, 1(3), 215-239.

Govers, R. M., &

Schoormans, J. L. (2005).

Product personality

and its influence on consumer preference. Journal

Of Consumer Marketing, 22(4),

189-197. doi:10.1108/073637605106053081

Maehle,

N., Otnes, C., & Supphellen, M. (2011). Consumers’

perceptions of the dimensions of brand personality. Journal

Of Consumer Behavior, 10(5),

290-303. doi:10.1002/cb.355

McPherson,

M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M.

(2001). Birds of

a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annual Review Of Sociology, 27(1), 415.

Parker, B. T. (2009).

A comparison of brand personality and brand user-imagery congruence. Journal Of

Consumer Marketing, 26(3), 175-184.

Simpson, P.A.,

& Stroh, L.K. (2004). Gender differences:

Emotional expression and feelings of personal inauthenticity. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 89(4),

715-721.

Sirgy, M. (1982). Self-Concept in Consumer Behavior:

A Critical Review. Journal Of

Consumer Research, 9(3), 287-300.

Witt,

R. E., & Bruce, G. D. (1972).

Group influence and brand

choice congruence. Journal of Marketing

Research,

9(4),

440-443.

Wood, L.

(2004).

Dimensions of

brand

purchasing behavior: Consumers in the

18–24 age group. Journal of Consumer

Behavior, 4(1), 9-24.

Zboja, J. J., & Voorhees,

C. M. (2006). The impact of brand trust and satisfaction on retailer repurchase intentions. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(6), 381-390.

Annex 1

Participants

Demographics

Annex 2

Interview

in EGONET

Part I. Ego’s Personal Information

1.

Participant’s gender.

2.

Participant’s age.

3.

How many times a week, approximately,

do you attend to this brand’s

stores?

Brand love scale (Likert Scale, 5

points)

1.

How much do you love to go to this brand’s

stores?

2.

How good does going to this brand’s

stores make you feel?

3.

How happy does going to this brand’s

stores make you feel?

4.

How much of this brand fan do you consider yourself?

5. When you are searching for a coffee shop, how often do you wait until you find this brand’s

store instead of going to the first coffee

shop you see?

6.

Do you feel this brand is worth the higher price?

Part II. Network Information

Now, please mention

15 persons that you consider

are your closest

relationships. You can mention

friends, family and people from different

groups and activities you have.

Characteristics

of each Alter:

1. Age

2.

Gender

3. Type

of relationship: Family, friend,

work friend, other.

4.

How important is this person for you.

5.

How many times a week do you see this person.

6.

How frequent to you attend this brand’s

stores with this person?

7.

How much do you think this person loves this brand?

Part III. Relationship Information

Between

actors - for each pair of alters:

1.

How likely is that these two persons interact or relate among them without you

being present?

|

Annex 3

Correlation Analysis

|

|

|

|

EF

EA

|

CABL

|

AGBL

|

EBL

|

|

EF Pearson Correlation

|

.244**

|

.104*

|

.343**

|

.478**

|

|

Sig. (2-tailed)

|

o

|

0.011

|

o

|

o

|

|

N

|

600

600

|

600

|

600

|

600

|

|

EFEM Pearson Correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

|

.321** 0.034

o 0.411

|

.120**

0.003

|

.338**

o

|

.529**

o

|

|

N

|

600

600

|

600

|

600

|

600

|

|

EA Pearson Correlation

|

.244**

|

.119**

|

.222**

|

.249**

|

|

Sig. (2-tailed)

|

o

|

0.003

|

o

|

o

|

|

N

|

600

600

|

600

|

600

|

600

|

|

CABL Pearson Correlation

|

.104* .119**

|

|

.116**

|

.193**

|

|

Sig. (2-tailed)

|

o 0.003

|

|

0.004

|

o

|

|

N

|

600

600

|

600

|

600

|

600

|

|

AGBL Pearson Correlation

|

.343** .222**

|

.116**

|

|

.557**

|

|

Sig. (2-tailed)

|

o o

|

0.004

|

|

o

|

|

N

|

600

600

|

600

|

600

|

600

|

|

EBL Pearson Correlation

|

.478** .249**

|

.193**

|

.557**

|

|

|

Sig. (2-tailed)

|

o o

|

o

|

o

|

|

|

N

|

600

600

|

600

|

600

|

600

|

|

Note: **Correlation is significant

|

at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

|

|

|

|

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level

(2-tailed)

EF= Ego Frequency, EA= Ego Age, CABL= Central Alter Brand Lave, AGBL=Alter

Gender Brand

Lave, EBL=Ego Brand Love

Annex 4

Regression Brand Love Model

Regression Brand Love Model

Annex 5

Regression analysis-ANOVAb

Regression analysis-ANOVAb

![]() Keywords: brand love, reference groups, social network analysis, homophily, centrality.

Keywords: brand love, reference groups, social network analysis, homophily, centrality.