probabilities, suggesting the need for future research

on the operational dynamics of startups and accelerators across

different country groups. This research opens avenues for further studies on

the mediating and moderating effects of IC components on performance,

particularly in the context of human capital and financial constraints, thereby

addressing gaps in the literature and expanding our understanding of startup

survival determinants in emerging economies.

Keywords: Accelerator Programs, For-Profit New Venture in

emerging markets, Intellectual Capital Dimensions

JEL CODE: L26, O34, C250

Introduction

The Object of Study

The importance of

new businesses for regional and economic growth has been recognized since

Joseph Schumpeter’s 1934 work, “The Theory of Economic Development” (Del Sarto

et al., 2020). Scholars, practitioners, and policymakers acknowledge that

startups significantly contribute to economic expansion, job creation, and

societal prosperity (Audretsch et al., 2006; Pradhan

et al., 2020).

These nascent

ventures face operational, competitive, resource, and planning challenges that

threaten their long-term survival. Startups are especially prone to failure in

their early years, with a 30% failure rate within the first two years

(Santisteban & Mauricio, 2017; Picken, 2017). This risk diminishes over

time (Yang & Aldrich, 2017), but factors like inexperienced management, low

trust and legitimacy, and inconsistent strategy make them vulnerable in the

early stages (Noboa, 2022).

The survival of

new firms can be examined through three main factors: personal attributes,

firm-specific characteristics, and the external environment (Brüderl et al., 1992). Various elements often challenge

survival, including limited financial resources (Smilor,

1997) and an inexperienced founding team (Gruber et al., 2008).

While the existing

literature on startup survival is ample, it is often limited to a single

theoretical perspective, region, or industry (Andreeva & Garanina, 2016; Cressy, 1996; Gimmon

& Levie, 2010; Baum & Silverman, 2004). Most studies have been

conducted in advanced economies like Europe, North America, and Asia, focusing

less on emerging economies (Azeem & Khanna, 2023). Empirical research

primarily uses regression-based models, especially Logistic Regression Models

(LR), to examine the relationship between various antecedents and outcomes,

often considering internal resources and non-financial performance measures.

Given the limited

scope of past research, future studies should prioritize cross-country analyses

and the impact of initial conditions entrepreneurs face in emerging markets.

The rise of startups in these economies and the growing body of research on

startup survival present numerous opportunities for new investigations. These

studies can explore the interplay between internal and external factors

affecting startup survival in emerging markets. Therefore, it is essential to

include emerging countries in such research endeavors.

The Impact of

Initial Conditions on the Companies’ Performance

Predicting new venture performance based on initial

observable factors is a key interest for entrepreneurship researchers, as it

can optimize resource allocation and benefit both entrepreneurs and society

(Dahlqvist et al., 2000).

Startup survival has been extensively studied from

various theoretical perspectives. Azeem & Khanna (2023) highlight the

Resource-Based View (RBV) as the most frequently cited perspective, which

serves as the basis for our study. RBV posits that a company’s unique,

valuable, difficult-to-replicate, and irreplaceable resources and capabilities

confer a competitive edge and enhance performance (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney,

1991). Among these resources, Intellectual Capital (IC) is particularly

crucial, as it is an intangible asset closely linked to a company’s strategy

and longevity (Rossi et al., 2016).

Our research, grounded in Barney et al., (2001) RBV

and Human Capital Theory (Becker, 1964; Mincer, 1974), emphasizes the pivotal

role of individual expertise and abilities in driving economic productivity.

Consistent with Cooper et al. (1994), we argue that a company’s initial

financial resources and human capital are fundamental to its survival,

especially for nascent enterprises (Van Praag, 2003).

This perspective underscores the critical contribution of both tangible and

intangible resources possessed by founding teams to the success of a startup (Strotmann, 2007).

Research Purpose

Our study focuses

on startups, which are catalysts of innovation and economic growth. We aim to

explore the impact of initial financial resources and Intellectual Capital (IC)

on startup development during the crucial pre-seed phase. This phase involves setting

business goals, identifying challenges, establishing market positioning, and

formulating strategic plans (Wong et al., 2005).

Nascent

enterprises often turn to accelerator programs for financial backing and expert

advice at this stage (Radojevich-K & Hoffman,

2012). Our study examines the correlation between the IC contributed by the

founding team—including their skills, knowledge,

experience, relationships, and abilities—and the survival rate of budding

for-profit ventures (Beckman & Burton, 2008).

In this context,

“startups,” also known as “nascent for-profit ventures,” are organizations

created in unstable environments to exploit new market opportunities (Davidsson

& Honig, 2003). Our research aims to determine how a founder’s initial IC

affects these ventures’ survival chances in emerging countries.

We seek to answer:

In the context of emerging countries, what is the impact of a startup’s IC on

its economic and financial performance? This question is vital as it

underscores the role of IC in determining a startup’s future. This study

focuses on startups in global accelerator programs, using data from the

Entrepreneurship Database Program (EDP) at Emory University, part of the Global

Accelerator Learning Initiative (GALI, 2020). The EDP, launched in 2013,

studies the causal effects of accelerating impact-oriented ventures. It uses

standardized questions that all participating accelerators incorporate in their

application processes, enhancing responsiveness and allowing observation of

nearly the entire pool of serious applicants. Program managers also track which

applicants join their programs (Lall et al., 2020). These programs value the IC

of the founders according to their selection criteria (GALI, 2021).

Most studies on

startup survival focus on developed countries (Azeem & Khanna, 2023), while

startups in emerging countries have not been widely analyzed. Our research

addresses this gap by considering geographic and socio-economic diversity. We

recognize the lack of comprehensive studies on startups in emerging economies

(Andreeva & Garanina, 2016) and aim to rectify

this. Our study broadens the scope by investigating the impact of IC—comprising

both initial financial resources and intangible knowledge—on the growth of

startups worldwide, with a particular emphasis on the pre-seed stage of

accelerator programs.

This study uses a

Logistic Regression Model to evaluate how different factors influence the

survival probabilities of startups in our sample. This model also predicts the

likelihood of a startup’s success in its early stage. We aim to enhance the

understanding of how IC affects the success of pre-seed startups, especially in

accelerator programs. This study has implications for various stakeholders.

Policymakers could use this knowledge to design policies that promote startup

growth by highlighting the value of IC, creating a dynamic and prosperous

startup ecosystem. Accelerator programs and venture capitalists could use this

knowledge to improve their startup selection and support processes, increasing

the success rate of the startups they back. Practitioners, such as startup

founders and employees, could use this knowledge to focus on building and

improving their IC.

The structure of

the remaining sections of the study is as follows: The second section

establishes the relevant literature that supports the conceptual framework and

hypotheses under study. The third section discusses materials and methods,

followed by the estimation results and their discussion. The validation of the

proposed hypotheses substantiates the next section, and the last section

addresses the practical and academic implications of the study and directions

for further research.

Literature review and hypotheses statement

Our analysis

investigates how a firm’s founding conditions affect its performance,

particularly its longevity. Various perspectives have examined this topic.

Organizational Ecology suggests that firms with superior initial resources are

more likely to survive through natural selection (Hannan & Freeman, 1977;

Fuertes-Callén et al., 2022; Romanelli, 1989). Other

research highlights the enduring impact of strategic choices made at the

outset. For instance, Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven (1990) demonstrated that founding

teams have a lasting influence on firm performance. Similarly, Cooper et al.

(1994) found that initial financial and human capital are strong predictors of

firm performance and survival. Kimberly (1979) also argued that environmental

conditions, the founder’s personality, and initial strategic choices

significantly shape organizational behavior.

The Entrepreneurial Context

Entrepreneurship

is a dynamic process involving team formation and adaptation to meet customer

demands. Salamzadeh and Kesim (2015) liken business

development to a life cycle, encompassing idea conception, prototype

development, market entry, product sales, and job creation. Wong et al. (2005)

identify the preparation for the start-up stage as the initial phase of defining

emerging ventures. Bruderl and Schussler (1990)

suggest that early survival signifies success, while sustained endurance

indicates adaptability in later stages.

The impact of initial conditions on

companies´ performance

The Resource-Based

View (RBV) posits that a founder’s attributes and circumstances significantly

impact venture performance. Dencker et al. (2009) found that knowledge

positively influences startup survival in Germany, with founders’ cumulative

experience enhancing knowledge integration. Research shows a varied positive

correlation between talent and performance, depending on a country’s

macroeconomic development (Furlan, 2019; Mayer-Haug et al., 2013). Studies also

demonstrate a differentiated positive impact of talent across entrepreneurial

stages and economic contexts (Kerrin et al., 2017). However, these effects can

be non-linear, contingent on factors like business development stages, survival

duration, administrative maturity, technological orientation, funding sources,

performance measures, and specific country and sector conditions (Delmar &

Shane, 2006).

Human Capital

Theory suggests that an individual’s human capital—education, work experience,

and job training—is vital for achieving organizational goals, securing a

competitive edge, and enhancing financial performance (Becker, 1994; Unger et

al., 2011). Gimmon and Levie (2010) applied this

theory to examine how founder qualities affect the ability to attract external

investment and ensure the survival of new high-tech firms. Their research

underscores that a founder’s managerial experience and academic credentials are

more critical in attracting external investment than technological expertise.

Cooper et al.

(1994) distinguished four types of initial capital: general human capital,

management expertise, industry-specific knowledge, and financial capital.

General human capital includes knowledge that increases productivity and access

to network resources. Management expertise is tacit knowledge from previous

general management experience. Industry-specific expertise, also tacit, is

essential for understanding the context of suppliers, competitors, and

customers. Financial capital serves as a cushion and allows strategic

flexibility.

This study

leverages RBV and Human Capital Theory, building on Cooper et al.'s findings,

to propose that initial allowances of financial and human capital are reliable

predictors of new venture survival (Van Praag, 2003).

Intellectual Capital

Intellectual Capital (IC), a concept widely

acknowledged despite its lack of a precise definition (Bontis,

1998), gained prominence with the rise of knowledge-based assets. Initially, IC

was quantified as the difference between market and accounting values (Brennan

& Connell, 2000). The modernization of the Human Capital (HC) concept by

Gary Becker in 1993 reignited academic interest in HC (Nyberg & Wright,

2015). The RBV paradigm signals a shift from physical and financial resources

to intangible assets (Spender, 1996; Abeysekera, 2021), positioning IC as a

strategic resource for emerging technological ventures (Juma & McGee,

2006).

This study defines IC as an

organization’s intangible assets, based on Stewart’s (1997) concept of IC as

“packaged useful knowledge”. These assets include employee knowledge,

adaptability, customer and supplier relationships, brands, intellectual

property, product trade names, internal processes, and R&D capabilities.

These assets are not in traditional financial statements, but they create

future value and competitive advantage. IC, as intangibles in financial

statements, often shows values three to four times higher than their book

values (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997).

The Three Dimensions of Intellectual

Capital in Entrepreneurship

Bontis (1998) suggests a research framework with three dimensions of

Intellectual Capital (IC): Human, Social, and Structural. This framework, which

views IC as valuable interconnected elements, explains IC’s dimensions (Marr

& Moustaghfir, 2005). It also enables the

empirical examination of IC components’ impact on performance (Felício, et al.,

2014).

Human capital (HC)

attributes, such as education and experience, are associated with small

business success (Baptista et al., 2014). Financial intermediaries and venture

capital firms value entrepreneurial experience highly when assessing startups,

using managerial skills and experience as primary selection criteria (Piva

& Rossi-Lamastra, 2018). HC is crucial in knowledge-based companies (Bosma

et al., 2004), and the value of specific human capital is evident in new

business founders’ entrepreneurial experience, especially among habitual

entrepreneurs who have previously founded at least one business (Baptista et

al., 2014).

Relational Capital (RC), or

Social Capital (SC), is an intangible asset that values relationships. It

involves cultivating, preserving, and enhancing quality relationships with

entities such as individuals, organizations, or groups that can impact business

performance (Welbourne & Pardo-del-Val, 2009).

RC encompasses the

knowledge derived from relationships with stakeholders like customers,

suppliers, and industry associations. This knowledge influences the

organization, adds value, and strengthens its operations. These relational

networks serve as crucial business resources, enabling entrepreneurs to tap

into resources otherwise unavailable within their venture (Bandera &

Thomas, 2018; Burt, 2017).

A significant aspect of SC

is the reputation, experience, and contacts facilitating entrepreneurs'

financing access (Baum & Silverman, 2004). New ventures can improve their

financing conditions through effective communication with investors and customers

(Gardner & Avolio, 1998).

Structural Capital (STC) is

recognized in the literature as the company’s internalized knowledge. It

pertains to the organizational structure and systems that bolster employee

productivity (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997). It encompasses all non-human intangible

assets of an organization. This includes culture, philosophy, internal

processes, information systems, databases, organizational charts, process

manuals, software, planning, strategies, routines, technology, and intellectual

property rights such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights. The value of these

assets to the company surpasses their material worth (Abdulaali,

2018). Intellectual property is often the only source of competitive advantage

for knowledge-based companies McGee & Dowling, 1994). Structural capital

focuses on organizational efficiency and its value derives from internal

infrastructure, processes, and culture on the one hand and from the adaptative

and development strategies adopted by the company on the other (Brennan &

Connell, 2000).

Impact of intellectual capital on the

performance of start-ups. Empirical evidence.

The Resource-Based View

(RBV) theory highlights Human Capital (HC) as a crucial determinant of firm

performance (Barney et al., 2001). HC, characterized by knowledge, is both

valuable and challenging to replicate. Studies have demonstrated a positive correlation

between knowledge-based intangibles and performance (Kellermanns

et al., 2016; Davidsson & Honig, 2003).

Coff (1997) provided

moderate evidence supporting HC as a strategic resource. Contradictory findings

could be due to factors such as path dependence, the inability of

cross-sectional studies to capture delayed effects, and the efficiency of the

labor market for specific forms of HC (Coff, 1997).

Both general and specific

forms of human capital have been identified as influential in a startup’s

performance (Cressy, 1996; Gimmon & Levie, 2010).

Bosma et al. (2004) found that investments in general, industry-specific, and

entrepreneurship-specific human capital significantly enhance startup survival,

profitability, and employment.

Research is scarce on the

impact of initial intellectual capital on the performance and survival of new

ventures in emerging countries, particularly during the pre-seed phase and

within high-impact acceleration programs. Most existing studies focus on startups

in developed countries and specific industries (Azeem & Khanna, 2023). This

gap necessitates further validation across a broader spectrum of startups,

highlighting the importance of our study.

Intellectual capital,

comprising knowledge, skills, and experience, is vital to a startup’s success,

especially during the pivotal pre-seed phase. Current research insufficiently

covers this aspect, particularly for high-impact startups and those in acceleration

programs. Most studies center on startups in developed countries, creating a

knowledge void about startups in diverse geographical contexts. They also tend

to focus on specific sectors, failing to capture the broader startup ecosystem

(Andreeva & Garanina, 2016). Therefore, it’s

crucial to broaden the research scope to include startups from various

locations, sectors, and development stages for a holistic understanding of

intellectual capital’s impact on startup performance and longevity.

The

nature of the problem under study

Our research focuses on

startups, the drivers of innovation and economic growth. We aim to investigate

the impact of a startup’s initial financial resources and intangible assets,

collectively known as Intellectual Capital (IC), on its development during the

crucial pre-seed phase. This phase involves founders setting business

objectives, identifying potential hurdles, establishing market positions, and

devising strategic plans.

We particularly examine new

ventures in emerging markets that seek financial aid and expert advice through

accelerator programs. Our goal is to explore the correlation between

IC—encompassing the founding team’s skills, knowledge, experience, relationships,

and capabilities—and the survival rate of nascent for-profit ventures.

In this study, we define

“start-ups” and “nascent for-profit ventures” as organizations formed in

volatile environments to exploit new market opportunities. Our main objective

is to determine how a founder’s IC affects these ventures’ survival prospects.

Our key research question

is: “How does a start-up’s intellectual capital stock influence its economic

and financial performance in emerging countries?” Answering this question is

vital, as it underscores the critical role of IC in shaping a start-up’s future.

Hypothesis Statement

To validate our hypothesis, we utilize a Logistic

Regression Model. This model quantifies the impact of several factors on the

survival probabilities of startups in our sample and predicts their success

likelihood during the critical pre-performance phase.

We aim to deepen the understanding of Intellectual

Capital (IC) in driving startup success, particularly within accelerator

programs in diverse geographical and socio-demographic contexts of emerging

markets. The findings could significantly impact founders, investors, and

policymakers, aiding in the design of programs that effectively support and

nurture emerging ventures.

By ensuring startups are equipped

with the necessary resources and enriched with appropriate skills and knowledge

from the outset, we can significantly enhance their chances of success and

longevity in the competitive business landscape.

Materials and methods

This study examines the impact of initial Intellectual

Capital (IC) intangibles on the survival of startups in emerging countries

during their pre-performance phase. For this purpose, the startups analyzed

were part of a subset that applied to accelerator programs and were sourced

from the Entrepreneurship Database Program (EDP) using survey data.

The Sample

EDP Characteristics

This study analyzes data

from a global cohort of entrepreneurs who applied to impact-focused

accelerators between 2013 and 2019. The data,

collected by Emory University’s Entrepreneurship Database Program (EDP),

includes application details and biannual follow-up survey results. After

removing duplicates and incomplete surveys, the EDP compiled a dataset of

14,457 new for-profit ventures. These ventures applied to approximately 370

programs run by over 130 organizations, with half being based in the United States,

Mexico, India, and Kenya. For this study, we focus on a subset of 4,106

ventures (28.4% of the total) that operate in countries classified as

upper-middle-income by the World Bank, which we define as emerging countries.

The EDP collected data at

the application stage and a year later from both successful and unsuccessful

applicants. The surveys, split into two sections, contain 91 questions. The

initial section includes contact information, entrepreneurship details, impact

metrics, operating model, financing, founding partners’ characteristics, and

understanding of new venture accelerators’ benefits. The follow-up section

gathers information about entrepreneurship goals, impacts, financial and

operational details, financing, and involvement in new venture accelerator

programs. The application data offers preliminary insights into the ventures,

founding teams, and pre-program performance.

Key issues for ventures in the initial EDP sample

Our analysis of the EDP

sample, which includes 14,457 for-profit ventures from 164 countries, reveals a strong social orientation and success

biases. Ventures that have been operational for at least three years

show a survival rate of 31% at the time of application, with over half

generating revenue and 78% expanding their workforce beyond the founding

members. Notably, 58% of these companies operate on proprietary technology.

About one-third of these

ventures have secured external equity investment, while a quarter have taken on

debt for startup expenses. Philanthropic contributions support a larger

portion. Ventures led by female founders are less likely to secure equity investments

but have a higher likelihood of having positive revenues in the preceding year.

Over 10% of the ventures in the sample are directed by women.

Ventures led by experienced

entrepreneurs or those with previous company founding experience tend to

attract more equity investments and report revenues and employees in the

preceding year. Similarly, ventures with founders who hold patents, copyrights,

or trademarks also show a higher tendency to attract equity investments and

report revenues and employees in the preceding year.

However, as expected, the

sample may exhibit a selection bias, as program selectors often favor ventures

with more established records (Hallen et al., 2020). Participants in these

programs are significantly more likely to report revenues in the preceding year

(GALI, 2020; GALI, 2021).

Procedures,

variables, and models

We performed an Exploratory

Factor Analysis (EFA) to examine the initial operational conditions of startups

in our dataset. This analysis accounted for both country

and startup conditions. We aimed to understand the interplay between specific

economic conditions, the venture’s operations, and the initial distribution of

founders’ intangible intellectual capital.

Following the work of Bontis (1998) we sought

to identify these factors in our dataset and evaluate their impact on the

startups’ survival probabilities.

We chose thirteen variables

from two primary sources: the World Bank Development Indicators (WDI) and the

Entrepreneurship Data Program at Emory University (EDP). The WDI supplied four

variables that mirror the economic conditions of each country, including

broadband subscriptions, control of corruption, rule of law, and internet usage

as a percentage of the population (World Bank, 2023). The EDP provided nine

variables associated with the initial allocation of founders’ intellectual

capital intangibles. These variables included factors like the founders’

previous for-profit experience, the venture’s social media presence, and

ownership of patents, inventions, copyrights, and trademarks. Table 1 presents

the descriptive statistics for these variables.

Table

1

Descriptive Statistics for Variables in the Principal Components

Calculations

|

Factorable Variables |

Type |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

|

Hast Twitter Account

(Y/N) |

Binomial |

0.40 |

0.49 |

|

Has LinkedIn Page (Y/N) |

Binomial |

0.31 |

0.46 |

|

Invention Based Model

(Y/N) |

Binomial |

0.58 |

0.49 |

|

Has Patents (Y/N) |

Binomial |

0.14 |

0.35 |

|

Has Copyrights (Y/N) |

Binomial |

0.14 |

0.34 |

|

Has Trademarks (Y/N) |

Binomial |

0.34 |

0.47 |

|

Broadband subscriptions

(per 100 people) |

Numeric |

14.27 |

13.01 |

|

Rule Law |

Numeric |

0.21 |

0.94 |

|

Corruption |

Numeric |

0.03 |

0.97 |

|

Internet (%

population using the Internet) |

Numeric |

54.87 |

27.75 |

|

F1FPEXP (Has FP

Experience) |

Binomial |

0.69 |

0.46 |

|

F2FPEXP (Has FP

Experience) |

Binomial |

0.57 |

0.50 |

|

F3FPEXP (Has FP

Experience) |

Binomial |

0.55 |

0.50 |

Notes: N: 14,457. Source: Own Elaboration

The analysis identified five primary factors (Table 2): F1 Country

Context (economic, infrastructure, and legal conditions), F2 Specific Human

Capital (founders’ entrepreneurial experience), F3 Social Capital (social

networks), F4 Structural Capital (patents or invention-based models), and F5

Market Rights (trademarks or copyrights). While product innovation often

results in patents and copyrights, the analysis initially differentiated

between Structural Capital and Market Rights. However, these two components can

be associated with Organizational Capital, which includes copyrights, patents,

procedures, rules, and decision-making aids (Abdulaali,

2018).

The test results confirm the suitability of the factor analysis. The

Composite Reliability Indices exceed the recommended threshold of 0.7. The

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure, which evaluates the sample’s adequacy, achieved a

value of 0.70, surpassing the suggested minimum of 0.6. This suggests that the

sample is appropriate for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test for sphericity was

statistically significant, with a p-value less than 0.001. The five components

extracted, detailed in Table 2, account for 70% of the total variance. Notably,

Factors 2 through 5 align with the IC classification criteria according to

existing literature.

Table 2

Exploratory factor analysis (N=14,457)

|

Source |

Label/explanation |

F1 Country Context |

F2 HCS |

F3 SC |

F4 STC |

F5 Market Rights |

|

WB |

Broadband subscriptions (per 100 people) |

0.95 |

|

|

|

|

|

WB |

Control of corruption (WB estimate) |

0.95 |

|

|

|

|

|

WB |

Rule of Law (WB estimate) |

0.94 |

|

|

|

|

|

WB |

Internet (% population using the Internet) |

0.89 |

|

|

|

|

|

Emory |

Founder 1 For Profit Experience (Y/N) |

|

0.80 |

|

|

|

|

Emory |

Founder 2 For Profit Experience (Y/N) |

|

0.73 |

|

|

|

|

Emory |

Founder 3 For Profit Experience (Y/N) |

|

0.72 |

|

|

|

|

Emory |

Venture has a LinkedIn Page (Y/N) |

|

|

0.84 |

|

|

|

Emory |

Venture has Twitter Acct (Y/N) |

|

|

0.83 |

|

|

|

Emory |

Venture has Patents (Y/N) |

|

|

|

0.80 |

|

|

Emory |

Venture has an Invention-Based Model (Y/N) |

|

|

|

0.77 |

|

|

Emory |

Venture has Copyrights (Y/N) |

|

|

|

|

0.81 |

|

Emory |

The venture has Trademarks (Y/N) |

|

|

|

|

0.73 |

|

|

Eigenvalues |

3.72 |

1.90 |

1.38 |

1.21 |

1.01 |

|

|

Variance |

28.49 |

14.62 |

10.60 |

9.31 |

7.70 |

|

|

Cumulative Variance |

28.49 |

42.87 |

53.47 |

62.78 |

70.48 |

|

|

Composite Reliability Index |

0.96 |

0.80 |

0.82 |

0.76 |

0.75 |

Notes:

For interpretative purposes, variables with factor loadings below 0.5 were not

included in the report. Extraction method: Principal component analysis.

Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization. Source: WB = World Bank

Development Indicators; Emory = Emory Entrepreneurship Database Applications

Surveys. Source: Own Elaboration

Variables

in the Logistic Regression Model

The two most frequently used non-financial startup

performance measures are survival (Brüderl, 1998; Mas-Verdú

et al., 2015; Wamba et al., 2017; Adams et al., 2019), and growth (Haeussler et

al., 2019; Vanderstraeten et al., 2016). To provide

empirical validation for our research question and working hypotheses, we

selected Survival as our dependent variable (DV), a binomial variable that

takes the value 1 if the startup remains in operation three years after its

inception and zero otherwise (Hyytinen et al., 2015).

Regarding our predictive

variables, we focus on the influence of the founding teams’ IC intangibles on

the startups’ likelihood of survival, as categorized by three types: human

capital, organizational or structural capital, and social capital (Bontis, 1998; Wang & Chang, 2005; Yang & Lin,

2009).

Our Logistic Regression model integrates the initial

Intellectual Capital endowments, utilizing principal components extracted from

an Exploratory Factor Analysis (Aguilera et al., 2006). The resulting variables

are “F2 SHC Experience”, which reflects the founding team’s for-profit venture

experience; “F3 SC Media Presence” (Bandera & Thomas, 2018), indicating the

entrepreneur’s network via LinkedIn and Twitter (Song & Vinig,

2012), and two components, “F4 STC Innovation” and “F5 Market Rights” (Alvarez-Salazar & Seclen-Luna,

2023), related to the venture’s Structural or Organizational Capital, covering

aspects like intellectual assets, databases, organizational culture, structure,

patents, and trademarks (Abdulaali, 2018).

New business survival

depends on three key categories: personal, business-specific, and environmental

factors (Brüderl et al., 1992). To study the impact

of a venture’s initial Intellectual Capital (IC) endowment, we consider the

inclusion of various factors such as external economic conditions, team

dynamics, and venture specifics. Recognizing their influence on survival

probability, we include these factors as control variables in our analysis.

The “F1 Country Context” factor includes

country-specific variables (Economic Context) derived from World Bank

Indicators (WBI). These variables reflect the national economic environment

faced by startups.

To examine the impact of alleviating financial

constraints, which indirectly reflects the quality of the founder’s team on

survival probabilities (Fuertes-Callén et al., 2022;

Lee & Zhang, 2011; Wamba et al., 2017), we include the categorical variable

“Has Debt.” This variable is coded as follows: 0 indicates that the venture did

not receive any debt financing; 1 indicates that the venture obtained debt financing

either at its inception or in the year following the application; and 2

signifies that the venture secured financing on both occasions. The “Has Debt”

variable is crucial for understanding how financial constraints and access to

debt financing impact the survival probabilities of startups. The presence of

debt financing can indicate a startup’s financial health and its ability to

secure external funding, which positively influences survival probabilities.

Access to debt financing provides necessary resources for growth, operational

costs, and financial challenges, enhancing survival chances, especially in

early stages. It also indirectly reflects the quality and credibility of the

founder’s team, as lenders typically assess the team’s experience, skills, and

business plan before extending credit. Additionally, debt financing offers

operational flexibility, allowing startups to make strategic investments and

respond to market changes more effectively, which is crucial for long-term

survival and success.

Business accelerators significantly contribute to the

facilitation of new venture creation. Start-ups seek top-tier accelerators to

expedite their developmental journey (Salamzadeh

& Markovic, 2018). These accelerators provide early-stage funding

and essential mentorship, driven by their confidence in the startup’s

potential, personal interest in the concept, or admiration for the

entrepreneurial team (Radojevich-Kelley &

Hoffman, 2012). The characteristics of accelerator programs are known to

influence venture performance. Although we cannot explicitly measure specific

accelerator characteristics, we will account for program-specific unobserved

heterogeneity in our subsequent analyses, thereby indirectly accommodating

program differences.

The EDP examines two key variables related to

accelerator program characteristics: participation, which refers to ventures

that completed the program (GALI, 2021), and the program impact area,

indicating whether the program has a specific impact area (Lall, Chen, &

Roberts, 2020). Additionally, the analysis includes the use of an impact

measure, specifically the B Lab GIIRS (Global Impact Investing Rating System),

which assesses the social and environmental impact of companies and funds.

Impact measures, such as the B Lab GIIRS, are crucial for startup survival as

they assess the social and environmental impact of companies. These measures

help startups attract impact investors, enhance their credibility, and align

with sustainable business practices, leading to increased funding

opportunities, customer loyalty, and long-term success.

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics

for the variables included in the logistic regression model.

Table 3

Descriptive Statistics for Variables in the LR Model

|

Source |

Variable/Label |

Type |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min. |

Max |

|

EDP Coded |

DV Success

(Survival) |

Binomial |

0.3 |

0.46 |

0 |

1 |

|

EDP Factored |

F2 SHC (Experience) |

Numeric |

0.28 |

1.00 |

-3.09 |

1.81 |

|

EDP Factored |

F3 SC (media presence) |

Numeric |

-0.19 |

0.97 |

-3.61 |

2.68 |

|

EDP Factored |

F4 STC (Innovation) |

Numeric |

0.195 |

1.00 |

-2.57 |

4.50 |

|

EDP Factored |

F5 (Market

Rights) |

Numeric |

-0.24 |

0.96 |

-4.47 |

2.72 |

|

WBI Factored |

F1 Country Context |

Numeric |

-0.04 |

0.37 |

-3.48 |

1.20 |

|

EDP Coded |

Has Debt |

Categorical |

0.19 |

0.54 |

0 |

2 |

|

EDP Survey |

participated# program

impact area |

|||||

|

0 1 |

Binomial |

0.27 |

0.44 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

1 0 |

0.14 |

0.35 |

0 |

1 |

||

|

1 1 |

0.05 |

0.23 |

0 |

1 |

||

|

EDP Survey |

use impact measure |

Binomial |

0.06 |

0.25 |

0 |

1 |

Notes:

Binomial Variables are assigned a value of 1 when present and 0 when absent.

For Debt Presence, the categorical values are assigned as follows: a value of 1

is given if an investment is present either at inception or at the end of the

last calendar year, a value of 2 is given if an investment is present at both

inception and the end of the last calendar year, and a value of 0 is given in

all other cases. Source: Own Elaboration

Estimation

Techniques

For the validation

of our hypothesis, we use a Logarithmic Regression model (LR) which is

considered suitable when the response variable is dichotomous, and the effect

of predictors is linear. Our LR Model relies on the reduced form model: ![]() Where

Where ![]() is the expected

value of

is the expected

value of ![]() given

given![]() (Aguilera et

al., 2006), In this case

(Aguilera et

al., 2006), In this case ![]() is the

probability of survival as a function of a set of available information about

the ventures. The analysis of the effects of the dimensions of IC over of

success as they´re operationalized requires a technique that adequately manages

the probabilities of attaining a successful performance. Logistic regression

(LR) is the appropriate technique when dealing with the relationship between a

dichotomous outcome and a set of explanatory variables. When a LR model estimates

a binary response outcome, we assume that its logit transformation has a linear

relationship with the predictor variables. Thereby the relationship between the

response variable and its covariates is interpreted through the odds ratio from

the parameters of the models. Measured in odds ratio (OR), if the parameter in

the regression is positive, the OR>1, and if its negative OR<1,

indicating the effect of the IV over the chances of survival. The logistic

regression model can be written as in equation 1:

is the

probability of survival as a function of a set of available information about

the ventures. The analysis of the effects of the dimensions of IC over of

success as they´re operationalized requires a technique that adequately manages

the probabilities of attaining a successful performance. Logistic regression

(LR) is the appropriate technique when dealing with the relationship between a

dichotomous outcome and a set of explanatory variables. When a LR model estimates

a binary response outcome, we assume that its logit transformation has a linear

relationship with the predictor variables. Thereby the relationship between the

response variable and its covariates is interpreted through the odds ratio from

the parameters of the models. Measured in odds ratio (OR), if the parameter in

the regression is positive, the OR>1, and if its negative OR<1,

indicating the effect of the IV over the chances of survival. The logistic

regression model can be written as in equation 1:

![]() =

= ![]()

![]() …

…![]() Equation 1: LR Model

Equation 1: LR Model

The binary response variable ![]() being either 0

or 1, and

being either 0

or 1, and ![]() .Then

.Then ![]() is interpreted

as

is interpreted

as ![]() for a given

combination of values of the predictor variables

for a given

combination of values of the predictor variables ![]() . We express the model as:

. We express the model as: ![]() , where

, where ![]() , could only assume two values depending on whether

, could only assume two values depending on whether ![]() is equal to

zero or one. The left-hand side of equation (1) is the log odds ratio, that is,

the logarithm of the odds that

is equal to

zero or one. The left-hand side of equation (1) is the log odds ratio, that is,

the logarithm of the odds that ![]() will equal 1,

for a given combination of the predictor variables. Our estimation uses the

Maximum Likelihood (ML) method.

will equal 1,

for a given combination of the predictor variables. Our estimation uses the

Maximum Likelihood (ML) method.

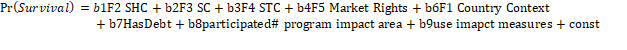

The Proposed Model

To validate our hypothesis,

the following logistic regression model (LR) is proposed.

Equation 2: Proposed LR Model

Results from the LR model and discussion

Academic literature

identifies various factors influencing the survival of new companies, operating

in emerging markets, in their pre-performance phase (Strotmann, 2007; Santisteban &

Mauricio, 2017). Our research focused on understanding the impact of

recognized intangible Intellectual Capital (IC) dimensions on this survival. We

integrated control variables into our Logistic Regression (LR) model to

mitigate potential confounding effects. This method aimed to distinctly assess

the influence of IC dimensions on Survival Probabilities, thus facilitating the

effective validation of our working hypothesis.

Table 4 shows the results

of the Logistic Regression (LR) Model, which we used to test our hypothesis.

This hypothesis proposes a positive link between the initial Intellectual

Capital of the founding team and the performance of the startups operating in

emerging countries in our sample.

Table

4

LR Model

Results for Startups in Emerging Countries

|

(DV) Survival |

Odds |

Robust |

z |

P>z |

[95% Conf |

Interval] |

|

Ratio |

SE. |

|||||

|

IC Components |

||||||

|

F2 SHC (Experience) |

1.09 |

0.04 |

2.37 |

0.018** |

1.02 |

1.17 |

|

F3 SC (media presence) |

1.13 |

0.05 |

3.10 |

0.002** |

1.05 |

1.23 |

|

F4 STC (Innovation) |

1.31 |

0.06 |

6.32 |

0*** |

1.20 |

1.42 |

|

F5 (Market

Rights) |

1.11 |

0.04 |

2.73 |

0.006*** |

1.03 |

1.20 |

|

Control Variables |

||||||

|

The Business Environment |

||||||

|

F1

Country Context |

2.10 |

0.31 |

4.96 |

0*** |

1.57 |

2.81 |

|

Finances |

||||||

|

Has Debt |

2.01 |

0.13 |

11.01 |

0*** |

1.77 |

2.27 |

|

Program Characteristics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interaction Effects Participated

#Has program impact area |

||||||

|

0 1 |

1.26 |

0.11 |

2.62 |

0.009*** |

1.06 |

1.49 |

|

1 0 |

0.97 |

0.11 |

-0.24 |

0.81 |

0.78 |

1.21 |

|

1 1 |

2.19 |

0.33 |

5.17 |

0*** |

1.62 |

2.94 |

|

use impact

measures |

1.08 |

0.17 |

0.47 |

0.64 |

0.79 |

1.47 |

|

constant |

0.31 |

0.02 |

-21.36 |

*** |

0.28 |

0.35 |

Notes: ***p < .01, **p < .05, *p <

.10; Robust SE = Robust Standard Errors

Source: Own Elaboration

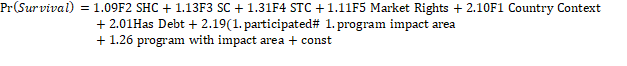

The resulting LR Model

The model’s results, expressed in terms of

odds ratios (expb), are as follows:

Equation 3: Estimated LR Model

The logistic regression model demonstrates a good fit

with the data, as indicated by the Wald chi2(10) value of 298.93 (p-value =

0.0000), suggesting overall statistical significance. The model explains

approximately 7.04% of the variance in the dependent variable (Success), as

reflected by the Pseudo R2 value. Key variables significantly impacting startup

survival include Has_Debt (Odds Ratio = 2.0074,

p-value = 0.000), (F1) Country Context

(Odds Ratio = 2.0986, p-value = 0.000), (F2) SHC (Odds Ratio = 1.0911, p-value = 0.018), F3 SC

(Odds Ratio = 1.1323, p-value = 0.002), F4 STC (Odds Ratio = 1.3101, p-value =

0.000), and Market Rights (F5), (Odds

Ratio = 1.1116, p-value = 0.006). Interaction terms show that participating in

a program with a specific impact area significantly increases the odds of

success (Odds Ratio = 2.1852, p-value = 0.000).

The analysis of odds ratios reveals several

significant variables impacting startup survival. At the 0.01 significance

level, Innovation (F4 STC), Market Rights (F5), (F1) Country Context, Has_Debt, and the interaction

effect of participating in a program with a specific impact area (1 1) are

significant. At the 0.05 significance level, Experience

(F2 SHC) and Media Presence (F3 SC) are significant. Additionally, the

interaction effect of participating in a program without a specific impact area

(0 1) is significant at the 0.01 level. These findings underscore the

importance of innovation, market rights, country context, financial health, and

targeted accelerator programs in enhancing startup survival.

By employing a Logistic Regression (LR) model, we were

able to measure the influence of various independent variables on the survival

probabilities of startups in the EDP sample. This also resulted in a predictive

model that can be used to determine the likelihood of success for a startup

during its pre-performance phase. The model correctly classified 72.4% of the

companies that survived. It had a sensitivity of 18.83%, indicating its ability

to correctly identify successful startups, and a specificity of 94.97%,

reflecting its ability to correctly identify unsuccessful startups. The

probability cutoff point was approximately 0.28. The area under the ROC curve

(0.6776) indicates a fair level of discrimination between successful and

unsuccessful startups

Discussion

Our analysis underscores the pivotal role of project

financing in shaping startups’ survival probabilities. Specifically, easing

financial constraints significantly increases a startup’s survival odds in the

pre-performance phase. Cooper et al. (1994) demonstrated that the total amount

of capital invested by the time of the first sale positively impacts the growth

and survival of new ventures. The literature widely acknowledges the

significance of startup capital for fledgling firms in their early stages (Cabral

& Mata, 2003; Figueroa-Armijos, 2019). Our empirical evidence suggests that

the most impactful control factor is the easing of these financial constraints.

During the pre-performance phase, ventures that have procured financing through

debt agreements (Has Debt) at inception, in the preceding year, or both,

demonstrate a 100% increase in survival likelihood (odds ratio 2.1) compared to

those constrained by external financing. These results align with other studies

that recognize the positive effect of debt financing on longer survival times

and higher revenues (Cole, 2018).

Our research highlights the significant role of

accelerator programs, particularly those with a well-structured curriculum, in

enhancing the survival probabilities of startups. We found a non-linear

interaction effect between variables indicating program completion and focus on

a specific impact area. Notably, when both indicators are present, the survival

probabilities of the venture increase by 119%. This is consistent with the

findings of Venâncio and Jorge (2022), who found that accelerated startups have

higher external equity ratios than non-accelerated startups, enhancing their

survival and growth probabilities. These findings also relate to the positive

effect of the entrepreneurial focus of EDP’s participating accelerator programs

on high-impact projects (Lall et al., 2020; GALI, 2021). The use of impact

measures increases the probabilities of survival by 8%, consistent with the

studies of Silva et al. (2022).

The study reveals that the wider economic environment,

as measured by WDI variables, increases survival probabilities by 110%. While

emerging countries are well-represented in the sample, the EDP primarily

reflects the entrepreneurial ecosystem in developed nations, particularly the

United States. This finding highlights the significant influence of the overall

economic context, suggesting that future research should explore the

operational dynamics of startups and accelerators across different country groups.

After evaluating the influence of both external and

internal variables from the EDP sample, we now turn our attention to the impact

of initial IC inventories on startup survival probabilities. These inventories

encompass three dimensions: Human Capital, Social Capital, and Structural or

Organizational Capital. Our primary focus is to validate, in our sample, the

hypothesis that the initial intangible IC assets of founding teams enhance

survival probabilities during the pre-performance phase.

According to our estimates, the SC assets identified

by the F3 SC (media presence) factor increase survival probabilities by 13%.

This result is generally consistent with the studies of Bandera and Thomas

(2018) and specifically aligns with the findings of Song and Vinig (2012), who associate positive performance in the

initial stages of ventures with expanded social media networks, particularly on

LinkedIn and Twitter.

The Structural or Organizational Capital (STC)

identified as F4 STC (Innovation) in the EDP sample, as indicated by variables

such as patent ownership and the adoption of invention-based models, increases

survival probabilities by 31%. This finding aligns with existing studies and

the fact that most ventures in the sample (58%) adopt an innovative-based

business model (GALI, 2020). It also corresponds with the natural selection

bias of acceleration programs in our sample (Radojevich-Kelley

& Hoffman, 2012), aligning with the idea that most accelerators want

concepts that have large upside potential that can be scaled to meet national

or global demand (Hallen et al., 2020).

In line with the F5 factor (Market Rights), owning

copyrights and trademarks enhances a venture’s survival chances of 11%. This

aligns with Abdulaali’s (2018) findings, which

highlight the positive impact of structural capital components on survival. It

also reflects the sample composition, where 33% of the ventures studied possess

trademarks and 13% have copyrights.

The founding team's experience in creating previous

for-profit ventures significantly influences survival probabilities, increasing

them by 9%. Prior studies have highlighted the capabilities that founders bring

to a venture due to their previous knowledge and experience, such as education

and industry experience (Bosma et al., 2004; Brüderl

et al., 1992; Geroski et al., 2010).

After incorporating control variables, empirical

evidence validated the general working hypothesis, demonstrating the positive

impact of the three dimensions of Intellectual Capital (IC) as recognized in

the existing literature and identified in the EDP sample. These dimensions,

represented by the intellectual capital assets of the founding teams,

significantly influence survival probabilities during the pre-performance

phase.

Our findings suggest several

implications for accelerator programs. First, accelerators could refine their

selection criteria to prioritize startups with strong intellectual capital

(IC), enhancing the likelihood of selecting ventures with higher survival

rates. Tailored support services, such as specialized training and mentorship,

could further develop the IC of participating in startups. Effective resource

allocation, focusing on educational workshops, can also be crucial.

Additionally, adopting new performance metrics to track the development of

founders’ skills and knowledge over time could better capture the impact of IC

on startup success. Accelerators might also advocate for policies supporting IC

development and consider expanding their programs to emerging markets, thereby

fostering a more inclusive global startup ecosystem.

Conclusions

This research builds on previous studies to examine

the influence of initial Intellectual Capital (IC) on the survival

probabilities of new ventures in accelerator programs operating in emerging

countries. It confirms the beneficial impact of IC assets on their survival, a

crucial success indicator for new ventures in the pre-performance phase, as

highlighted in broader contexts by Unger et al. (2011) and Sardo and Serrasqueiro (2019).

While most existing studies on startup survival have

been confined to advanced economies and have employed a single theoretical

approach (Azeem & Khanna, 2023), this research bridges the gap by

highlighting the significance of initial IC for startups in impact accelerator

programs in emerging countries. It shows that these IC accumulations,

encapsulating useful and applicable knowledge identified in surveys, enhance

the survival prospects of startups in the EDP-focused sub-sample. This

enhancement remains even after accounting for potential unobserved

heterogeneity and considering both external and internal influences on startup

operations. By examining the role of initial IC in a diverse range of

early-stage ventures in acceleration programs, the research expands our

understanding of startup survival determinants and broadens its scope to

encompass emerging economies and diverse accelerator programs.

Our findings are not just a result but a starting

point for further research. Future studies using the EDP information will

analyze the impact of knowledge intangibles on survival probability under

specific conditions, including socio-demographic coverage, heterogeneity of

acceleration programs, founding team composition, diversity, operational

sectors, size, funding source diversity, and differentiated effects. They will

also consider the contribution to the development of the countries where they operate,

and the innovation processes generated from their operation.

Additionally, there is a significant opportunity for

complementing this research. Due to the scarcity of studies analyzing the

mediating and moderating effects of IC components on performance, future

research will consider these complementary effects (Delmar & Shane, 2006),

particularly the relationships between human capital and financial constraints

as suggested by the research of authors such as Unger et al. (2011) and Salamzadeh et al. (2023). The lack of interaction studies

in this area highlights a gap in the literature, presenting a valuable avenue

for future exploration to better understand these dynamics.

Implications of the study

By implementing these practical strategies, startup

founders can better navigate the challenges of the initial stages and improve

their chances of long-term success. Our study underscores the importance of

early recognition and investment in key factors such as Intellectual Capital

(IC), financial planning, and participation in accelerator programs for startup

founders. By prioritizing the development of IC assets, including the knowledge

and skills of the founding team, startups can build a solid foundation for

navigating the early stages. Securing diverse funding sources and establishing

clear financial goals from the outset can further mitigate financial

constraints and improve survival probabilities.

Engaging in well-structured accelerator programs

offers valuable resources, mentorship, and networking opportunities, enhancing

the startup’s resilience and performance. Our research contributes to this

understanding by demonstrating that these elements significantly influence

startup survival, particularly in diverse and globally oriented contexts. By

recognizing and leveraging these critical factors early on, founders can better

position their ventures for long-term success and growth, adapting to challenges

and capitalizing on opportunities as they arise.

For policymakers and accelerator program developers,

our findings provide valuable insights for refining selection processes and

program development. Leveraging data from the EDP and the predictive strength

of our Logistic Regression (LR) model, we offer preliminary guidance for

creating more effective mentoring and support initiatives. The clear

distinction between the values of specificity and sensitivity in our LR model

indicates that survival and failure probabilities are independent entities,

challenging traditional assumptions and uncovering new research opportunities.

Further investigation into these factors can enhance the efficacy of support

initiatives, benefiting the startup ecosystem by fostering more resilient and

successful ventures.

References

Abdulaali, A. (2018). The impact of

intellectual capital on business organizations. Academy of Accounting and

Financial Studies Journal, 22(6), 1–16.

Abeysekera, I. (2021). Intellectual capital and knowledge management

research towards value creation: From the past to the future. Journal of

Risk and Financial Management, 14(6), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060238

Adams, P., Fontana, R., & Malerba, F. (2019). Linking vertically

related industries: Entry by employee spinouts across industry boundaries. Industrial

and Corporate Change, 28(3), 529–550. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtz014

Aguilera, A., Escabias, M., & Valderrama,

M. (2006). Using principal components for estimating logistic regression with

high-dimensional multicollinear data. Computational Statistics & Data

Analysis, 50(8), 1905–1924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2005.03.011

Alvarez-Salazar, J., & Seclen-Luna, J.

(2023). To survive or not to survive: Findings from PLS-SEM on the relationship

between organizational resources and startups’ survival. In Partial least

squares path modeling: Basic concepts, methodological issues and applications

(pp. 329–374). https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-37772-3_12

Andreeva, T., & Garanina, T. (2016). Do

all elements of intellectual capital matter for organizational performance?

Evidence from Russian context. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 7(2),

397–412. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-07-2015-0062

Audretsch, D., Keilbach, M.,

& Lehmann, E. (2006). Entrepreneurship and economic growth. Oxford

University Press.

Azeem, M., & Khanna, A. (2023). A systematic literature review of

startup survival and future research agenda. Journal of Research in

Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 26(1), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRME-03-2022-0040

Bandera, C., & Thomas, E. (2018). The role of innovation

ecosystems and social capital in startup survival. IEEE Transactions on

Engineering Management, 66(4), 542–551. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2018.2859162

Baptista, R., Karaöz, M., & Mendonça, J.

(2014). The impact of human capital on the early success of necessity versus

opportunity-based entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 42, 831–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9502-z

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal

of Management, 17(1), 33–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Barney, J., Wright, M., & Ketchen, D. J.

Jr. (2001). The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. Journal

of Management, 27(6), 625–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700601

Baum, J., & Silverman, B. (2004). Picking winners or building them?

Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture

financing and performance of biotechnology startups. Journal of Business

Venturing, 19(3), 411–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00038-7

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical

analysis with special reference to education. Columbia University Press.

Becker, G. S. (1994). Human capital revisited. In Human capital: A

theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education (3rd

ed.). The University of Chicago Press. https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/human-capital-theoretical-and-empirical-analysis-special-reference-education-third-edition/human-capital-revisited

Beckman, C., & Burton, M. (2008). Founding the future: Path

dependence in the evolution of top management teams

from founding to IPO. Organization Science, 19(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0311

Bontis, N. (1998).

Intellectual capital: An exploratory study that develops measures and models. Management

Decision, 36(2), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251749810204142

Bosma, N., Van Praag, M., Thurik,

R., & De Wit, G. (2004). The value of human and social capital investments

for the business performance of startups. Small Business Economics, 23,

227–236. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000032032.21192.72

Brennan, N., & Connell, B. (2000). Intellectual capital: Current

issues and policy implications. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(3),

206–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930010350792

Brüderl, J. (1998). Network

support and the success of newly founded businesses. Small Business

Economics, 10, 213–225. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/a:1007997102930

Bruderl, J., & Schussler,

R. (1990). Organizational mortality: The liabilities of newness and

adolescence. Administrative Science Quarterly, 530–547. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393316

Brüderl, J., Preisendörfer, P., & Ziegler, R. (1992). Survival

chances of newly founded business organizations. American Sociological

Review, 227–242. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096207

Burt, R. (2017). Structural holes versus network closure as social

capital. In Social capital (pp. 31–56). https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315129457-2/structural-holes-versus-network-closure-social-capital-ronald-burt

Cabral, L., & Mata, J. (2003). On the evolution of the firm size

distribution: Facts and theory. American Economic Review, 93(4),

1075–1090. DOI: 10.1257/000282803769206205

Coff, R. (1997). Human assets and management dilemmas: Coping with

hazards on the road to resource-based theory. Academy of Management Review,

22(2), 374–402. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707154063

Cole, R. S. (2018). Debt financing, survival, and growth of start-up

firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 50, 609–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.10.013

Cooper, A., Gimeno-Gascon, F., & Woo, C. (1994). Initial human and

financial capital as predictors of new venture performance. Journal of

Business Venturing, 9(5), 371–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)90013-2

Cressy, R. (1996). Pre-entrepreneurial income, cash-flow growth and

survival of startup businesses: Model and tests on UK data. Small Business

Economics, 49–58. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00391975

Dahlqvist, J., Davidsson, P., & Wiklund, J. (2000). Initial

conditions as predictors of new venture performance: A replication and

extension of the Cooper et al. study. Enterprise and Innovation Management

Studies, 1(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/146324400363491

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human

capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3),

301–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6

Del Sarto, N., Isabelle, D., & Di Minin, A. (2020). The role of

accelerators in firm survival: An fsQCA analysis of

Italian startups. Technovation, 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2019.102102

Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2006). Does experience matter? The effect

of founding team experience on the survival and sales of newly founded

ventures. Strategic Organization, 4(3), 215–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127006066596

Dencker, J., Gruber, M., & Shah, S. (2009). Pre-entry knowledge,

learning, and the survival of new firms. Organization Science, 20(3),

516–537. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0387

Edvinsson, L., & Malone, M. (1997). Intellectual capital:

Realizing your company’s true value by finding its hidden roots.

HarperCollins Publishers.

Eisenhardt, K., & Schoonhoven, C. (1990). Organizational growth:

Linking founding team, strategy, environment, and growth among US semiconductor

ventures, 1978-1988. Administrative Science Quarterly, 504–529. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393315

Felício, J., Couto, E., & Caiado, J. (2014). Human capital, social

capital and organizational performance. Management Decision, 52(12),

350–364. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2013-0260

Figueroa-Armijos, M. (2019). Does public entrepreneurial financing

contribute to territorial servitization in

manufacturing and KIBS in the United States? Regional Studies, 53(3), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1554900

Fuertes-Callén, Y., Cuellar-Fernández, B., & Serrano-Cinca, C.

(2022). Predicting startup survival using first-year financial statements. Journal

of Small Business Management, 60(6), 1314–1350. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1750302

Furlan, A. (2019). Startup size and pre‐entry experience: New evidence from Italian new manufacturing ventures. Journal

of Small Business Management, 57(2), 679–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12427

GALI. (2020). The entrepreneurship database program at Emory University:

2019 year-end data summary. https://www.galidata.org/assets/report/pdf/2019%20Year-End%20Summary.pdf

GALI. (2021, May). Does accelerators work? https://www.galidata.org/assets/report/pdf/Does%20Acceleration%20Work_EN.pdf

Gardner, W., & Avolio, B. J. (1998). The charismatic relationship: A

dramaturgical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 32–58. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.192958

Geroski, P., Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (2010). Founding conditions and the survival of new firms. Strategic Management

Journal, 31(5), 510–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.823

Gimmon, E., & Levie, J.

(2010). Founder’s human capital, external investment, and the survival of new

high-technology ventures. Research Policy, 39(9), 1214–1226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.05.017

Gruber, M., MacMillan, I., & Thompson, J. (2008). Look before you

leap: Market opportunity identification in emerging technology firms. Management

Science, 54(9), 1652–1665. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1080.0877

Haeussler, C., Hennicke, M., & Mueller, E. (2019). Founder–inventors

and their investors: Spurring firm survival and growth. Strategic

Entrepreneurship Journal, 13(3), 288–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1326

Hallen, B., Cohen, S., & Bingham, C. (2020). Do accelerators work?

If so, how? Organization Science, 31(2), 378–414. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2019.1304

Hannan, M., & Freeman, J. (1977). The population ecology of

organizations. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 929–964. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/226424

Hyytinen, A., Pajarinen, M.,

& Rouvinen, P. (2015). Does innovativeness

reduce startup survival rates? Journal of Business Venturing, 30(4),

564–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.10.001

Juma, N., & McGee, J. (2006). The relationship between intellectual

capital and new venture performance: An empirical investigation of the

moderating role of the environment. International Journal of Innovation and

Technology Management, 3(4), 379–405. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219877006000892

Kellermanns, F., Walter, J.,

Crook, T., Kemmerer, B., & Narayanan, V. (2016). The resource‐based view in entrepreneurship: A content‐analytical comparison of researchers’ and entrepreneurs’ views. Journal

of Small Business Management, 54(1), 26–48. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jsbm.12126

Kerrin, M., Mamabolo, M., & Kele, T. (2017). Entrepreneurship

management skills requirements in an emerging economy: A South African outlook.

The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business

Management, 9(1), 1–10. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-9bea7314e

Kimberly, J. (1979). Issues in the creation of organizations:

Initiation, innovation, and institutionalization. Academy of Management

Journal, 22(3), 437–457. https://doi.org/10.5465/255737

Lall, S., Chen, L., & Roberts, P. (2020). Are we accelerating equity

investment into impact-oriented ventures? World Development, 104952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104952

Lee, J., & Zhang, W. (2011). Financial capital and startup survival.

Academy of Management Proceedings, 2011(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2011.65869494

Marr, B., & Moustaghfir,

K. (2005). Defining intellectual capital: A three‐dimensional approach. Management Decision, 43(9), 114–1128. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740510626227

Mas-Verdú, F., Ribeiro-Soriano, D., & Roig-Tierno, N. (2015). Firm

survival: The role of incubators and business characteristics. Journal of

Business Research, 68(4), 793–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.11.030

Mayer-Haug, K., Read, S., Brinckmann, J., Dew, N., & Grichnik, D. (2013). Entrepreneurial talent and venture

performance: A meta-analytic investigation of SMEs. Research Policy, 42(6–7),

1251–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.03.001

McGee, J., & Dowling, M. (1994). Using R&D cooperative

arrangements to leverage managerial experience: A study of technology-intensive

new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)90025-6

Mincer, J. (1974). The human capital earnings function. In Schooling,

experience, and earnings (pp. 83–96). NBER. https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c1767/c1767.pdf

Noboa, F.

(2022). Fuerza de carácter y continuidad emprendedora: Evidencia de Ecuador. Ciencias

Administrativas, 19, 2. https://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?pid=S2314-37382022000100002&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en

Nyberg, A., &

Wright, P. (2015). 50 years of human capital research: Assessing what we know,

exploring where we go. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(3),

287–295. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2014.0113

Picken, J. (2017). From startup to scalable enterprise: Laying the

foundation. Business Horizons, 60(5), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2017.05.002

Piva, E., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2018). Human capital signals and

entrepreneurs’ success in equity crowdfunding. Small Business Economics, 51,667–686.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11187-017-9950-y

Pradhan, R., Arvin, M., Nair, M., & Bennett, S. (2020). The dynamics

among entrepreneurship, innovation, and economic growth in the Eurozone

countries. Journal of Policy Modeling, 42(5), 1106–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2020.01.004

Radojevich-Kelley, N., &

Hoffman, D. (2012). Analysis of accelerator companies: An exploratory case

study of their programs, processes, and early results. Small Business

Institute Journal, 8(2), 54–70.

Romanelli, E. (1989). Environments and strategies of organization

start-up: Effects on early survival. Administrative Science Quarterly,

369–387. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393149

Rossi, C., Cricelli, L., Grimaldi, M., &

Greco, M. (2016). The strategic assessment of intellectual capital assets: An

application within Terradue Srl.

Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1598–1603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.024

Salamzadeh, A., & Kawamorita Kesim, H. (2015). Startup companies: Life cycle

and challenges. In 4th International Conference on Employment, Education and

Entrepreneurship (pp. 36–48). Belgrade, Serbia: EEE. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2628861

Salamzadeh, A., & Markovic,

M. (2018). Shortening the learning curve of media start-ups in accelerators:

Case of a developing country. In Evaluating media richness in organizational

learning (pp. 36–48). IGI Global. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-5225-2956-9.ch003

Salamzadeh, A., Tajpour, M., Hosseini, E., & Brahmi, M. (2023). Human

capital and the performance of Iranian digital startups: The moderating role of

knowledge sharing behavior. International Journal of Public Sector

Performance Management, 12(1–2), 1. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPSPM.2023.132248

Santisteban, J., & Mauricio, D. (2017). Systematic literature review

of critical success factors of information technology startups. Academy of

Entrepreneurship Journal, 23(2), 1–23. Sardo, F., & Serrasqueiro,

Z. (2019). On the relationship between intellectual capital and service SME

survival and growth: A dynamic panel data analysis. International Journal of

Learning and Intellectual Capital, 16(3), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLIC.2019.100537